The Path Forward With Controlled Environment Dentistry

| Parsa Zadeh, DDS, MAGD, FICOI—a Beverly Hills dentist specializing in implant and reconstructive dentistry for more than 30 years—shares his thoughts on how dental practices can treat patients safely. |

I was practicing dentistry before gloves were a ubiquitous part of dental care. It was a different era for infection control in the field—masks were only used to protect a patient from the operator’s breath, disinfection and sterilization rules were few, and eye protection was entirely optional. This practice lasted until the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) crisis of the mid-1980s, which brought a considerable shift in dental environmental safety measures. Rumors started about HIV transmission in dental offices, so the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and state dental boards acted decisively to calm fears. One particularly notable change was the requirement that all oral health professionals wear gloves during dental work. It was a difficult shift for many. I remember a professor of mine who cut off the fingers of his gloves so he could continue to experience the tactile sensation he was used to, while still adhering to the law. At the time, these new rules were considered inconvenient and costly to dentists, but the strict protocols for patient contact established by state dental boards and OSHA saved lives and instilled confidence in dental safety—for both patients and oral health professionals. In 2020, no patient avoids the dentist for fear of HIV infection, and no oral health professional fears exposure to it, as sterilization, disinfection, wearing gloves, and the use of eye protection have become an integral part of dental care.

Though the disease and its cultural context are entirely different from HIV, COVID-19 brings a similar crisis to dentistry, particularly regarding the environmental safety of the dental office. As of May 2020, some dental practices are beginning to reopen, but most oral health professionals (including me) are scared of the possibility of exposing themselves and their teams to this new viral enemy.

I do not think private dental practice can survive another 3 to 4 months of this uncertain climate. If dentistry’s strong and effective response to the HIV/AIDS crisis is any indication, we have serious work ahead of us, for we must evaluate, experiment, innovate and implement solutions. We must make the dental office safe again.

Current Status

This virus resides in the respiratory system and can spread through expiratory droplets. Unlike Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), the COVID-19 virus can be present in a totally asymptomatic individual either during the incubation and recovery period, or in those who are not even aware of the infection. In other words, for the near future, oral health professionals will have no idea whether the patient in our chair is carrying the infection or not. Perhaps, if a reliable and accessible instant test (5 to 10 minutes) becomes available, we can have every patient tested before he or she is seated in the dental chair.

Meanwhile, we cannot continue to postpone the practice of dentistry. We need to do the work, and our patients need to get their dentistry done. We must understand the following points to move forward.

For the foreseeable future, we may have an infected patient in our chair. As oral health professionals, we are the most vulnerable healthcare providers. If the virus exists in the mouth, any dental work that uses air, water, or a rotating bur can spatter the contaminated fluid out of the mouth and onto those close by. Even a denture adjustment has the potential of aerosolizing the moisture on the denture.

Wearing an N95 or KN95 mask does not protect us against contaminated aerosol. It may protect us from inhaling the virus, but COVID-19 will stay viable on the outside surface of not only the mask, but also the sides of our faces, the straps, our foreheads, and our necks for days. Hours after we remove the mask, we may inadvertently transfer the infection to our nose, eyes, or other areas vulnerable to viral infection. Additionally, if this virus can transfer through droplets in the air, it is possible that it travels through an HVAC system. I assure you that your building HVAC system does not have an N95-equivalent filter. In a multi-office building, there could be a sick person in a space next door, entirely outside of your control, who contaminates the return air that is, in turn, circulated to your suite. Intensive care unit personnel treating COVID-19 patients consider an intubations a high-risk procedure due to aerosol from the oropharynx. If simple proximity for less than a minute and inserting a tube through the oral cavity could be high risk, what are oral health professionals supposed to do to remain safe?

We sit close to the oral cavity, spray air and water into it, and agitate the mix with instruments at 200,000 to 400,000 cycles per minute, for hours at a time. Even holding strictly to strong sanitation and body protection protocol and treating mostly uninfected patients with a very small chance of infection present — it only takes one contagious patient to potentially transfer the infection to the entire team.

The Experiment

I set out the following experiment to find out how much the dental team is in danger of becoming contaminated from the oral fluids spattered during a dental procedure.

Goals:

To emulate dental procedure activities using a fluorescent dye to learn the extent and pattern of aerosol created by various dental procedures in their worst-case scenario.

To evaluate various methods that this aerosol can be minimized.

To configure a system that eliminates the risk of infection for the dental team.

Methods:

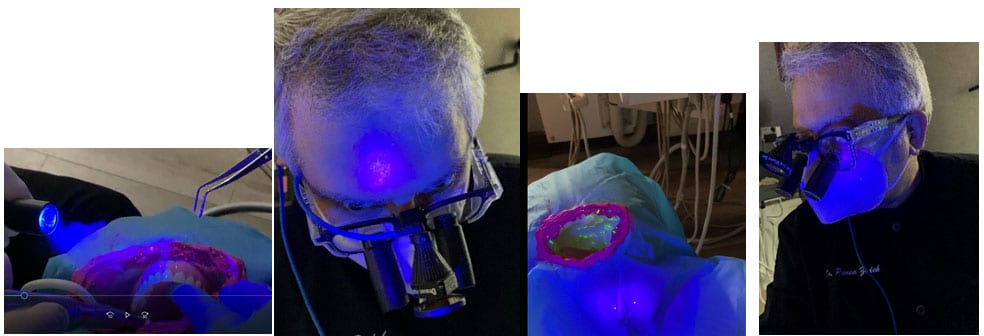

An artificial “oral cavity” is painted with fluorescent dye to represent viruses containing mucus and saliva. The dental team is dressed according to existing personal protective equipment (PPE) standards to protect against bloodborne pathogens. The dental handpiece and suction are used on artificial teeth inside of the cavity for various durations. The entire operatory and team members are examined by a black light to ensure a clean start. After each experiment, the location and amount of spatter noted by a black light are documented by photographs (Figure 1 and 2).

After the controlled environment is created, the most offensive procedure is repeated to evaluate the efficacy of the system. Recommendations are made accordingly with the goal of making dentistry safe again.

Discussion:

With an understanding of the above dangers, I was not comfortable treating even emergency patients. So I have adopted the following procedures so that my team and I feel safe treating our patients, and, in turn, our patients feel safe receiving dental care. Together I call these protocols “controlled environment dentistry.” These measures are needed in addition to the current PPE (gloves, masks, eye protection and maybe gowns and bouffant) due to the airborne nature of the virus and its viability for hours and days on inanimate surfaces.

Recommendations:

- Get yourself and all of your team members tested for COVID-19. If a test returns positive, isolate.

- Install a minimum efficiency reporting value (MERV) filter of 14 or higher in the HVAC registers for each space. A MERV rating tells you, on a scale of 1-16, how effectively your filter traps the small particles you don’t want circulating through your office. MERV 14 will remove particles as small as viruses from the air (Figure 3 and 4).

- Wear N95 masks or a double mask when within 10 feet of patients or team members. If your team or you are infected, you will not pass it to your patients or other team members.

- The administrative staff must wear at least a level 3 mask, at all times.

- Allow only one person at a time in the break room or restroom. Wait a minute or two before the next person goes into the same space.

- Dentists and those providing direct patient care (dental hygienists and dental assistants) should wear positive air pressure hoods (PAPH) that cover the entire head and neck while working in the oral cavity. They can be removed when greeting patients. The only way to keep airborne particles away from our head during a dental procedure is to create a positive atmosphere around our head and neck so that no particles can get close to our skin, mask and eye protection. The supplied air must come from a source at least 20 feet away where no one is breathing over it. The supply air is processed by a high efficiency particulate, or HEPA air filter, which is able to trap 99.97% of particles that are 0.3 microns.

- Sanitize all the hoods and other operatory surfaces against airborne and surface pathogens with ultraviolet (UV) radiation and ozone gas in treatment rooms. UVC-band wavelengths range from 220 to 280 nm. Longer wavelengths are not as efficient for disinfection. UVC radiation is harmful to all living organisms including humans. Therefore, these machines must be equipped with remote controls so they can be activated only when we are not in the room and deactivated before we enter the room. An open operatory design dental office would pose challenges to protecting team members against the UV radiation. While the UV radiation disinfects all surfaces that the light is shined upon, it can not reach the crevices of the dental upholstery and under surfaces of equipment. An ozone generator emits ozone gas that can travel to all areas of the room to achieve disinfection. Ozone gas can kill the SARS coronavirus and, as the structure of the new 2019-nCoV coronavirus is almost identical to that of the SARS coronavirus, it is relatively safe to say that it will also work on the new coronavirus. However, no studies have proven this yet. There is a current study on the efficacy of ozone gas against the novel coronavirus currently being conducted at the Institute of Virology in Hubei, China.

Conclusion

I hope you find this discussion of “controlled environment dentistry” helpful when you decide to open your practice or return to work.

good article Dr. Zadeh are you currently practicing with PAPH

where do you get the paph and merv

Why do I not see anything in print on the use of rubber during restorative procedures to control the amount of bacterial spray when using high speed handpieces??

Dr. Ken Neuman

Sorry – it should have said rubber dam.